|

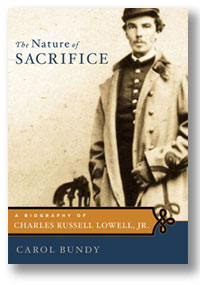

"Charles Russell Lowell [was] killed at Cedar Creek

two weeks short of his first wedding anniversary, one month

short of the birth of his child, and less than three months

before his thirtieth birthday. This was a man who in the Shenandoah

Valley campaign had had thirteen horses shot from under him,

a man whom, in three and a half years of battle, no bullet

had touched. And so when the spent minié bullet hit

him high in the chest, knocking him from his horse and reducing

his voice to a whisper, he had refused to leave the field.

At the summons to attack, he had been strapped back into his

saddle, and with sword drawn he had led the charge, his red

officer's sash making him an irresistible target for the rebel

sharpshooters on the rooftops of Middletown . . . News of

his death traveled fast. General George Custer, his fellow

brigade leader, cried. General Wesley Merritt, his division

commander, mumbled that he would give up his command if only

Lowell were there to receive it. General Philip H. Sheridan,

who owed to Lowell the rescue of his reputation on that day,

said, 'He was the perfection of a man and soldier.'"

—from the Introduction to The Nature of Sacrifice |

Rarely

in Union narratives do you find so compelling and romantic

a tale on which to hang a bit of history. I saw a biography

of Charlie Lowell as a chance to tell the story of the Civil

War from the point of view of the children of the Transcendentalists.

Steeped in idealism, these young men yearned for practical

applications, Lowell most of all. He believed that the world

advances by “impossibilities achieved.” The American

experiment in democracy was one; the abolition of slavery

would be another. Rarely

in Union narratives do you find so compelling and romantic

a tale on which to hang a bit of history. I saw a biography

of Charlie Lowell as a chance to tell the story of the Civil

War from the point of view of the children of the Transcendentalists.

Steeped in idealism, these young men yearned for practical

applications, Lowell most of all. He believed that the world

advances by “impossibilities achieved.” The American

experiment in democracy was one; the abolition of slavery

would be another.

|